All the Feels: Tuning-in to Emotions in Research

“Wow, that felt a little like therapy!” We hear this all the time from participants after spending an hour or two with them diving into a research topic.

In ethnographic and design research, you can’t separate opinions from the emotions that come with them. Extracting emotions in research is its own art form — given how complex human emotions can be.

As we keep adjusting to life in a Covid world, emotions continue to be unpredictable and highly variable. Even the most innocuous-seeming research topics, such as talking about your favorite TV show, are steeped in powerful emotions driven by all the changes happening in our world. Now more than ever, being well-practiced in sensing, feeling, naming and investigating emotions in research settings is essential for researchers.

When documenting feelings, whether they be of joy, discomfort, or anything in between, a more emotionally attentive approach is particularly useful to discern the most accurate insights.

THE WHEEL OF FEELS

Naming emotions can transform how we experience or understand them; names facilitate reflection upon our emotions and our responses to them. Consider hygge as a recent, imported example in the United States. Certainly English has words like “cozy” and “contentment,” but once we learned hygge, we could be more precise and intentional in describing the intersection of emotions and a sense of place. We had a new tool at our disposal to define and act upon, relate to our environments, and communicate the feeling of warmth and well-being that are the full hygge experience. But, given the seemingly endless range of human emotions, what do we do if we can’t just borrow a word from the Danes?

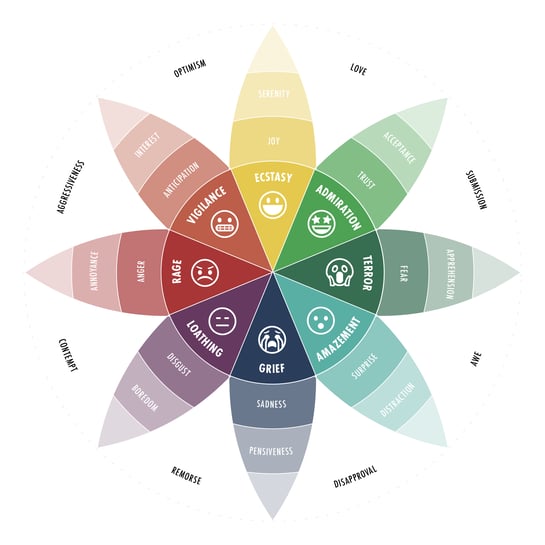

Developed by American psychologist Dr. Robert Plutchik, The Emotion Wheel highlights eight primary emotions that are the foundation for all other emotions and expands these basic feelings by association. Instead of attempting to pinpoint the specificity and nature of almost 34,000 human emotions, this framework presents a simplified model to help identify emotions.

Dr. Plutchick found patients were comfortable expressing the 8 basic emotions in the inner ring of feelings but found greater value in helping them question the specific root of the feeling. For example, “Anxious” and “Excited” may be right next to each other on the emotion wheel, bringing similar signals. Yet the root of these two emotions can make all the difference between someone feeling joy or terror. Understanding and articulating the differences and connections between these two things can lead to powerful insights.

Dr. Plutchick found patients were comfortable expressing the 8 basic emotions in the inner ring of feelings but found greater value in helping them question the specific root of the feeling. For example, “Anxious” and “Excited” may be right next to each other on the emotion wheel, bringing similar signals. Yet the root of these two emotions can make all the difference between someone feeling joy or terror. Understanding and articulating the differences and connections between these two things can lead to powerful insights.

The Emotion Wheel can help teams when language around emotions may be deeply nuanced. When building out a journey map or doing an affinity mapping exercise, a common mistake teams make is leading with the most basic emotions (happy, sad, confused). However, the further you get into your analysis and synthesis process, the more specific you will need to be to uncover something meaningful. Bringing clarity to your word choice of the emotions you’re using to describe a current or ideal experience can help teams identify a path forward.

And if the emotion wheel fails you, get out your thesaurus and get to work.

OBSERVING (or sensing) EMOTIONS

Emotions are invisible - or are they? The thought may have crossed your mind above, how do I get specific with naming emotions if users are holding back? Put simply, you look closely and ask better questions.

A trap that is easy to fall into as a researcher is falling solely into “listening” mode, taking rigorous notes, hanging on every word or quote given without looking up and watching how your participant is communicating through non-verbal cues. Facial expressions, long pauses, changes in tone and inflection are all their own critical “data streams'' to pay attention to in an interview. Tuning in to all of these details is absolutely essential, even when moderating over Zoom.

In practice, sometimes this requires an uncomfortable thing for the lead moderator: putting the pen and notebook down! Staying present and engaged in the discussion and listening with your whole body helps to sense the hidden emotions and micro-expressions. And if you need a little help identifying these, psychologist and micro-expression pioneer Paul Eckman has developed a robust facial coding and training program to detect these split-second emotional responses.

EMOTIONS AS METAPHORS Both the 5 Stages of Grief and The Grieving Curve were developed by Elizabeth Kubler-Ross. The five stages of grief model, also known as The Kübler-Ross model, was originally developed for terminally ill patients processing their approaching death.

Both the 5 Stages of Grief and The Grieving Curve were developed by Elizabeth Kubler-Ross. The five stages of grief model, also known as The Kübler-Ross model, was originally developed for terminally ill patients processing their approaching death.

However, grief takes many forms beyond palliative care contexts. Since its development, the stages of grief have been a common framework and metaphor for discussing cycles of negative emotions and trauma: from navigating addiction, receiving bad news or experiencing a setback to other seismic life changes. During the pandemic, a high school senior may have found themselves grieving the loss of rites of passage such as prom, homecoming attendance, or even senior skip day. While these changes were not life-threatening, they required processing grief for loss of what could have been, and will have a lasting impact.

This grief cycle and the visual depiction of the grieving curve as an up and down experience can provide a way to logically discuss feelings that tend to defy logic and feel untethered from reason or process. When seen within a framework of meaning, a better conversation can be had about what can be done to positively deal with change, regardless of the outcome.

With any research, humans are involved, which means emotions will be too. Using the methods above is a good starting point for any researcher looking to identify the emotions that are driving the “why” behind behaviors and beliefs.